The 1801 eruption of Hualālai Volcano, the big volcano that forms the western shore of this island, was preceded by an eruption in 1800, a little bit higher up on the mountain slope. The 1800 eruption broke out at about 6,000 feet elevation and made it to the ocean on either side of Kalaemanō, which is several miles north of Pā'aiea, in between two and three hours.

We know that because by 1800 there were already haole people living here. William Ellis traveled through in 1823, and 1800 was recent enough in people's memories that they were able to relate to him stories of that eruption. Because, you know, when Ellis and his party got to the land there, they thought that it was—when they were, some people were sailing offshore and they looked, they thought it was water over there because fresh pāhoehoe was so shiny. You know how we see mirages with the sky, the blue of the sky reflecting on even pavement as we're driving. So they thought that that was all water, but it wasn't. It's still shiny, fresh pāhoehoe.

Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, February 5, 1870

4. A i ka wā i puka aʻe ai ka lā a kiʻekiʻe iki aʻe, ua hoʻōho aʻe ia, “Nani kā hoʻi ka wai o kēia ʻāina e kahe maila, ʻeā!” Hōʻole ʻia mai ana e ka poʻe i ʻike, me ka ʻī ʻana mai, “ʻAʻole kēlā he wai, akā, he pāhoehoe wale nō kēlā, a no ka pā pono ʻana ihola o ka lā, hinuhinu ihola ka pāhoehoe, a kuhi hewa aku ai ʻoe he wai, he ʻaʻā wale nō ia āu e ʻike lā, a mai kuhi ʻoe ua like me kēia ʻāina me kou ʻāina, ka piha i ka wai mai ʻō a ʻō.”

4. Once the sun rose up a bit, he exclaimed, “Wow, how beautiful is the water flowing on this land!” This was refuted by those who knew, as they replied, “That is not water but all smooth pāhoehoe lava, and because the sun strikes it just right, the smooth lava glistens, leading you to mistake it for water, but it is actually just volcanic stone you see there, so do not assume this land is like your own, with water found everywhere.”

Courtesy of Awaiaulu, from the writings of John Papa ʻĪʻī

The Nature of Pāhoehoe

Another word for pāhoehoe is satin. So that shiny flowy nature that a silver satin fabric has is pāhoehoe. So in 1800, 6,000 feet to the ocean, two or three hours, it destroyed a small village. And I don't know that anybody lost their life, but it was further up the coast in an area even more unpopulated than Pā'aiea would've been then.

The 1801 Lower Eruption

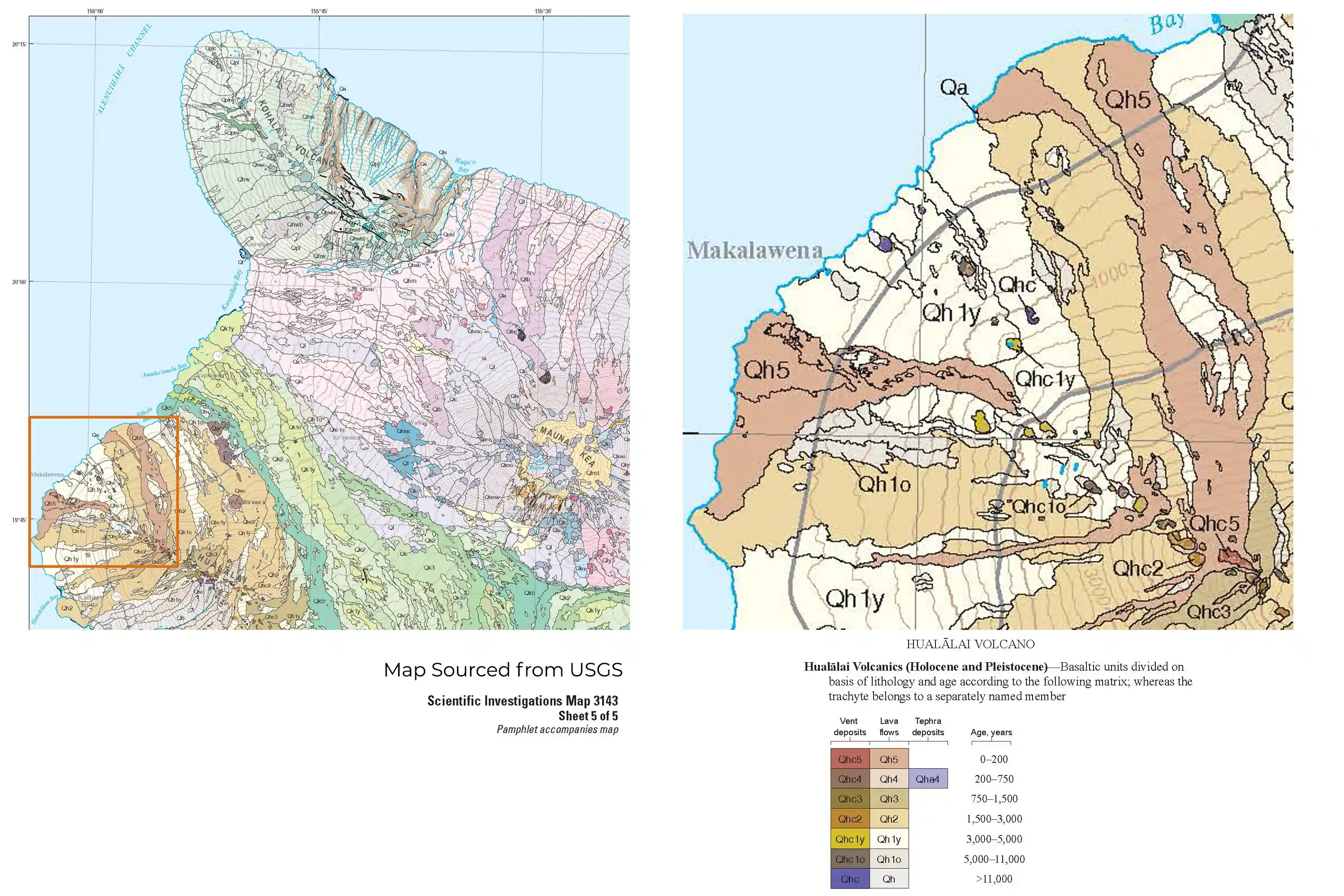

As usually happens with volcanoes in Hawaii, if you have an eruption up high in the rift, very frequently there'll be an eruption following lower on the rift zone. And that's exactly what happened in 1801 when at about an elevation of 2,000 feet instead of 6,000—we're down to 2,000 feet—an eruption began on the floor of an old crater called Kileo, just mauka of what is now the Māmalahoa Highway connecting Kailua and Waimea.

Just mauka of that road in Hu'ehu'e, an eruption began on the floor of this crater. And then according to accounts, the lava went under the road. So what's now the highway used to be a traditional trail that went from the uplands of Kona down to Kīholo. This is a little bit off topic, but it was named Keala'ehu, 'Ehu being a prominent chief of the South Kona District mostly.

The eruption began on the floor of Kileo, and then it went under the road and then surfaced up at a place near a little village called Manuahi. And that began a fountaining eruption that quickly made its way to the sea on the north edge of what we know today as the 1801 flow field.

"So they thought that that was all water, but it wasn't. It's still shiny, fresh pāhoehoe."

The Flow Sequence

The area at Ka'elehuluhulu and Mahai'ula, that lava flow happened early in the eruptive sequence of the 1801 flow. After that was in place over maybe a few weeks—you know, we don't really know, but just kind of judging what we know of Kīlauea eruptions and what it did for 35 years on the south slope of Kīlauea and watching Kalapana and, you know, the subdivision of Royal Gardens and all of that stuff get buried. We can kind of look at the lavas from the 1800 flow and get an idea.

During or right after the eruption of the high fountaining that made a spatter rampart called Puhiapele or the puhi or explosions of Pele, there was an eruption of a very different character. It was probably just an upwelling of lava, like an artesian well, no big fountaining. And that flow may have occupied an older lava tube for a short distance and then surfaced and started flowing down the southern edge of the first flow, if that makes any sense.

Entering Pā'aiea Pond

Eventually the southern flow made its way down to the coast and, you know, rather than ocean, it would've encountered the mauka-most edge of Pā'aiea pond, and then it would've made its way through the pond, going through the pond and then into the ocean and extending the edge of the land outward a little bit.

Keep in mind that offshore of Keāhole the bathymetry is really steep. Any lava trying to build outward on that shelf that I talked about earlier is probably not gonna be very possible. Because you need a foundation for the lava to advance outward. And if it's just a steep drop off there, all that's gonna happen is the broken rocks are just gonna keep falling and falling and falling, tumbling down the slope.

The Lava Tube System

And this is all pāhoehoe by the way. We know that because when we go and look now it's all pāhoehoe lava. Really smooth, billowy. There's one enormous lava tube that is crossed by the Queen Ka'ahumanu Highway, a big skylight that you can see immediately mauka of the road. That was the main conduit for getting lava down to the coast.

But even flowing through the quiet waters of Pā'aiea, it would've been slightly explosive as it got into deeper waters. The lava itself would for a time be flowing underwater. I had the privilege in early 1987 to watch a beloved pond called Punalu'u, which used to be in Puna near Waha'ula Heiau in Hawai'i Volcanoes National Park.

"I got hit a couple of times by perfectly shiny, little sharp bits of lava that flew out of the water."

Pūnālu'u was right outside the park boundary, and it was popularly called Queen's Bath. You know, if we believed the stories, the queen was a busy lady because there's queen's baths all over the islands. But the traditional name of Punalu'u Pond remains. And there was a heiau, or a place of worship, there also.

But I was there the night Punalu'u filled with lava from Pu'u'ō'ō. And I could watch the lava flowing under the water, and when it was doing that, it was imploding on itself. And just—I don't know how to describe, it's kind of like little fireworks, except they're exploding underwater. And a little burst of spatter would fly up into the air. I got hit a couple of times by perfectly shiny, little sharp bits of lava that flew out of the water.

So I would presume that, you know, after what I saw there, this is the same behavior over here because it's kind of the same water, the character and nature of the water—just still.

The Orange Oxidation

But while that's happening and the lava is advancing forward, on what used to be pond, the water in the back is still steaming, you know, even though it's covered by or being evaporated by the lava that's advancing. The steam that's happening is causing the iron in the lava, the iron content of our lava, to oxidize.

"When iron oxidizes or rusts, it turns orange."

And so you're gonna end up with a surface on that flow, or at the very least in the cracks that are formed in the pāhoehoe, orange, because when iron oxidizes or rusts, it turns orange. And the oxidation of the—you know, it's only 14% on average, the iron content of our lava. The iron content of our lava is about 14%.

And so when lava flows in water, especially a pond, or a still body of water, the steaming involved as the water boils off will cause a thermal oxidation of the iron content. And you'll end up with orange cracks forming on the surface of the pāhoehoe.

The Evidence Today

And so today, when we go and look, you know, either from the air via Google Earth, or you can just drive on the roadway and look over, you can see the low area below, you know, where the highway is, is a fairly flat plateau that extends out toward the north end of the runway. And it's got this orangeish or rust colored cast to it and, flying over, you know, you can see that, oh, that's all orange over there and that's where the water was for the pond because the ocean is still way over there. And to get an idea of the shoreline, Keāhole is old lava, you know, like I said, 1,500 years old or so.

Before and After the Flow of 1801

The exact interior layout of Pāʻaiea remains unknown. A historical account describe it as three miles long and a mile and a half wide, making it one of the largest fishponds in Hawaiʻi. At that scale, the pond likely incorporated multiple construction methods: seawalls connecting natural rock formations, anchialine pools providing freshwater, and islets dotting the interior. Fishermen traveled through the pond by canoe, using it as a shortcut to avoid paddling against the ʻEka wind and ocean currents. The orange-hued areas visible today mark where lava met water in 1801, but what lies beneath remains unknown, buried under many feet of multicolored lava rock.