Pele has an affinity for fish and fish ponds. Maybe she's just hungry and she wants to eat fish.

Photo above: Pele filling kapoho, June 4th 2018.

The 2018 Lower Puna eruption shocked the world with its devastating power, destroying over 700 homes and creating new land where communities once stood. But for those who understand Hawaiʻi's deeper geological and cultural patterns, the event revealed something profound about the relationship between volcanic forces and Hawaiian aquaculture—a pattern stretching back centuries.

On the east side of Hawaiʻi where it's wet, the windward coast, there are also fish ponds, but not as big as the ponds on the leeward coasts. In Puna, near the eastern tip of the island, instead of the western tip of the island, were ponds at a place called Kapoho and Pohoiki. Poho is the word for subsidence, or to subside.

The Geology of Subsidence

The name Kapoho itself tells the story of this landscape. Located at the intersection of Kīlauea's East Rift Zone and the Pacific Ocean, this area has been shaped by both volcanic creation and geological collapse for millennia.

And Kapoho is famous because of its location right on the eastern tip of the island where the East Rift Zone of Kīlauea volcano goes into the ocean. And so Kapoho is subject to subsidence as the rift zone becomes filled with lava and eruptions break out. The land extends seaward and may subside or collapse.

Also, the southern flank of Kīlauea is really heavy, and it also collapses episodically during big earthquakes when the weight of the land causes it to subside—boom—like quickly. And during a severe earthquake, something in the order of 6.0 or 7.0, would cause the land to fall. Or actually that's not correct. The land falling or collapsing is what causes the big earthquake. So the earthquake doesn't cause the land to fall. The falling causes the earthquake.

Historical Documentation

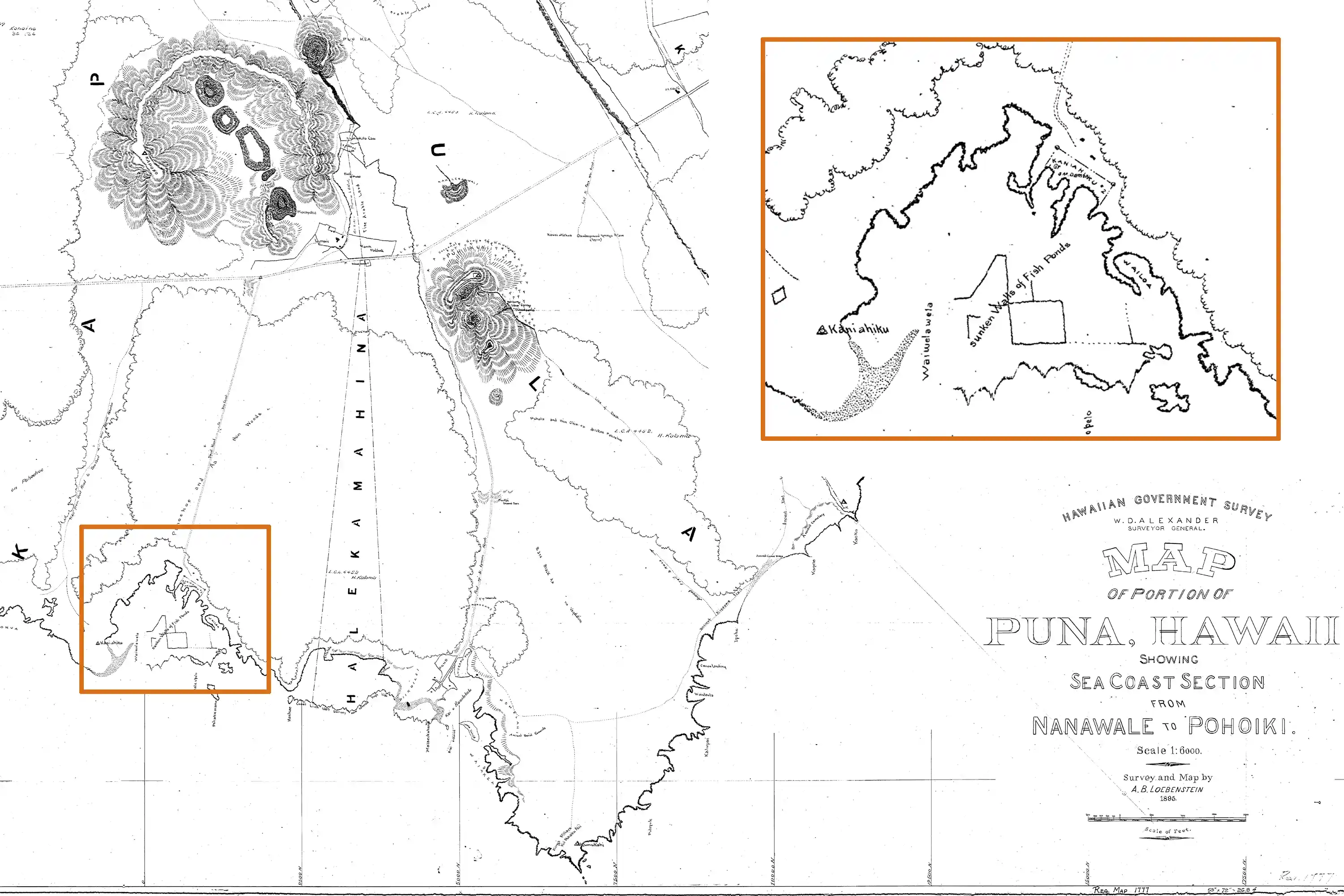

The instability of this coast wasn't just observed by modern geologists. Kingdom of Hawaiʻi surveyors documented the dynamic nature of Kapoho's fishponds in real time during the 19th century.

Now Kapoho—the subsidence and Pohoiki. We can go to old maps drawn in the 1870s or 1880s for this part of the island and see written "fish pond walls dry in 1870," and here we are four years later and the walls are awash in the ocean. So it's documented on paper, on a map by surveyors of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi, that the walls were subsiding of these ponds.

The 2018 Eruption

When Kīlauea's Lower Puna eruption began in May 2018, few anticipated that it would reveal ancient patterns about volcanic behavior and fishponds. The scale of the eruption was unprecedented in modern times.

I find it really fascinating that when Pele and the lava flow in 2018 moved down from the vent, the primary vent of the eruption, there was a huge river of lava because lots and lots of lava was being erupted, really high volume in a wide, wide river of lava.

The eruption created what geologists called a "lava river" carrying molten rock at unprecedented volumes toward the ocean. But it was the lava's behavior near Kapoho Cone that revealed something unexpected.

"Somehow Pele wanted her lake back. So she went and got it and then went back and then entered the ocean at Kapoho, right where a fish pond was."

Pele went toward the ocean and it went on the north side of Puʻuolekia, also known as Kapoho Cone. And held in the crater of Puʻuolekia, was a lake—a little pond or a lake called Waiapele, the water of Pele.

And it was absolutely fascinating because the pond is—the cone is like over here. The lava is coming down to go to the ocean, which is out there. But one branch of the lava flow made a U-turn and came up and filled in the lake there. And we can see it on aerial photos now that somehow Pele wanted her lake back. So she went and got it and then went back and then entered the ocean at Kapoho, right where a fish pond was. There are constructed walls of the fish pond in the ocean that we could still see.

The Pattern Revealed

So again, for the fourth time, I guess—Pāʻaiea, Kīholo, Wainānāliʻi, and Kapoho—from three different volcanoes: Hualālai, Maunaloa, and Kīlauea. Pele has an affinity for fish and fish ponds. Maybe she's just hungry and she wants to eat fish.

This pattern spans over two centuries and three different volcanoes:

- 1801: Hualālai lava fills Kamehameha's Pāʻaiea fishpond

- 1859: Maunaloa lava fills Kīholo and Wainānāliʻi fishponds

- 2018: Kīlauea lava fills Kapoho fishponds